Selective Inference: A useful technique for high-throughput biology

Background

The falling cost of sequencing technology has lead to a proliferation of biological datasets that are able to measure nuclear states such as relative amounts of protein expression via RNA-seq or targeted genotyping through next generation sequencing (NGS) platforms. These new technologies allow for hundreds of thousands to millions of measurements for a single individual. In principle, this data should help to elucidate the genetic basis of complex phenotypes ranging from human height to disease states. However, even with a large number of patients (possibly in a case-control setup) the ratio of measurements to observations will be large.

Suppose there are \(N\) patients, \(p\) measurements per patient, and \(m\) associated measurement types that actually impact the phenotype of interest (\(p-m>0\)). Then if a statistical test of comparing the phenotype difference for a given measurement is done univariately (one at a time), and assuming the tests are stochastically uncorrelated, a p-value threshold of \(\alpha\cdot 100\%\) will yield (on average) \(\alpha(p-m)\) false positives. Whether we also reject the null of no effect for the \(m\) true genetic factors will depend on the power of our study design. Imagine there are 500,000 measurements (\(p\)) only 100 true factors (\(m\)), and a p-value of 5%, then there will be an average of 24,495 false positives! If we are lucky enough to reject the null of the no effect for all the true genetic factors, then only 0.4% of the “significant” factors are truly significant.

To overcome this predicament, multiple hypothesis testing adjustments are made to ensure that the majority of “significant” variables are not only noise. The first, and more conservative, approach is to use family-wise error rate (FWER) adjustments which define a new p-value threshold such that probability of making at least one type I error on \(p\) hypotheses is no greater than \(\alpha\). The most conservative approach within the FWER adjustments is to use the Bonferroni correction, such that \(\alpha^{\text{bonfer}} = \alpha / p\). As the number of hypotheses grows, the harder it becomes a variable to be considered statistically significant. This poses the problem that more measurements can be non-optimal because the power of a test decreases as the nominal value of \(\alpha\) decreases. Let’s see an example

An alternative, and I think more popular, approach is to use false discovery rate (FDR) adjustments which ensure that the proportion of rejected null hypothesis which are false positives are less than or equal to \(\alpha\). Fundamentally, FDR leverages the fact that the distribution of p-values between 0-5% will be more left-skewed for hypotheses which are truly non-zero than those under the null (which are uniform). Of course for a fixed \(m\) as \(p\) increases the power of a FDR-adjusted test will decline, but by nowhere as quick a rate as the FWER approach. In summary, researchers in fields like genetics are well accustomed to adjusting the magnitude of their p-values to account the large number of hypotheses being performed and understand the trade-off between limiting false positives and diluting power.

A simple genetic model

Suppose there is some continuous phenotype \(y_i\) for individual \(i\) and we assume a linear genetic model, namely that the observed trait is governed by the impact of \(m\) genetic factors plus some individually-specific environmental phenomenon \(e_i\), then the variation in the phenotype would be characterized by the following formula:

\[\begin{align} y_i &= \sum_{k=1}^m x_{ik} \beta_k + u_i \hspace{3mm} i=1,\dots,N \tag{1}\label{eq:gen1} \\ \text{var}(u_i) &< \infty, \hspace{3mm} cov(u_i,u_j)=0 \hspace{1mm} \forall i\neq j \nonumber \end{align}\]We’re going to assume that the \(m\) causal variants are measured within the total of \(p\) measurements taken. This is a problematic assumption, because we know the positions chosen on a genotyping array are in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with many other variants, and surely some of them are causal.[1] As as \(\text{sign}(\text{cov}(y_i,x_{iA}))=\text{sign}(\text{cov}(y_i,x_{iB}))\) then their effect can be proxied through the measured position. However there is absolutely no reason to believe this would be the case, and the failure to measure all relevant positions may explain the missing heritability problem for complex diseases. However this issue is not the focus of this post.

In a genome wide association study (GWAS), many individuals with different phenotypes have their germline cells sequenced and genotyped[2], and the goal is to find the variants[3] that associate with the observable characteristic on interest. Equation \eqref{eq:gen1} could be a plausible genetic model estimated by data from a GWAS by encoding \(x_{ij}=\{0,1,2 \}\) for the number of alleles person \(i\) has (relative to some reference genome), and assuming an additive dominant genetic model.[4] Since a researcher observes \(x_i=\{x_{i1},\dots,x_{ip}\}\), has no idea which of the \(m\) variants are relevant (hence the need to do the study), and has more measurements than observations \(p \gg N\), equation \eqref{eq:gen1} cannot actually be estimated.

Instead researchers test for the association between the trait and a genetic locus one at a time, fitting the following model.

\[\begin{align} y_i &= x_{ik} \beta_k + e_i \hspace{3mm} i=1,\dots,N, \hspace{1mm} k=1,\dots,p \tag{2}\label{eq:gen2} \\ e_i &= \sum_{j\neq k}^m x_{ij} \beta_k x_{ij} + u_i \nonumber \end{align}\]When the relationship between genetic loci is independent, then there will be no bias in the estimate of \(\bhatk\), as can be shown by some simple algebra.

\[\begin{align} E(\bhatk) &= E\big( (\bxk' \bxk)^{-1} \bxk' \by \big) \nonumber \\ &= E \Bigg(\beta_k + \sum_{j\neq k}^m \frac{\bxk'\bxk \beta_k}{\|\bxk \|_2^2} + \frac{\bxk'\bu}{\|\bxk \|_2^2} \Bigg) \nonumber \\ &= \beta_k + \sum_{j\neq k}^m \gamma_{kj}\beta_k \tag{3}\label{eq:gen3} \end{align}\]Where \(\gamma_{kj}\) is the linear dependence between the genetic factors \(k\) and \(j\). Again, when the loci are all uncorrelated with each other \(\gamma_{kj}=0\) and \(E(\bhatk)=\beta_k\). Unfortunately equation \eqref{eq:gen2} is problematic because it is likely that some measured non-causal variants will be correlated with the measured ones, or that causal variants will be correlated with each other but with the opposite sign seen with respect to the phenotype. Despite these problems, univariate tests are popular by researchers according to Chiara Sabatti because:

- Computationally simplicity

- No imputations needed to fill missing variables in a design matrix

- Does not need to decide which correlated feature is more important (if they’re both good proxies)

- Makes p-value results that are comparable across studies (see discussion above for the various adjustment mechanisms) which can be used for meta-analyses later

Despite these advantages it nevertheless remains that correlated genotype positions and genetic relatedness between individuals will lead to biased results that could have been overcome by multiple linear regressions techniques such as generalized least squares had there been more individuals than measurements.

Selective inference: obtaining valid p-values via the Lasso

The Lasso is an \(\ell_1\) penalized regression model where the loss function is balanced by the l1-norm of the coefficients weighted by \(\lambda\). A continuous response will continue to be assumed.

\[\begin{align*} &\text{Least-squares Lasso} \\ \hat\beta^{\text{lasso}} &\in \arg \min_\beta \hspace{3mm} \frac{1}{N}\|y - X\beta \|_2^2 + \lambda \|\beta\|_1 \end{align*}\]For a given choice of \(\lambda\), the Lasso may shrink some feature coefficient values to zero. This begs the question, can the non-zero (or “selected”) features be tested in terms of statistical significance? At first glance, this seems highly improbable because they Lasso is an adaptive model, meaning our hypothesis would be following the data. Why? Because the support (i.e. non-zero values) of \(\hat\beta^{\text{lasso}}(\lambda)\) is only known after it has been estimated rather than before. If we knew which variables would be zero before we estimated the model, we wouldn’t have needed to include them![5] This idea of data snooping is well-known.

It is therefore quite surprising and delightful that despite being data-driven, the Lasso’s ex-post hypothesis tests for the model’s coefficients can still generate valid p-values. This is done through a new technique known as Selective Inference. Because the selection event of the Lasso can be characterized by a polyhedral constraint, a conditional distribution can be generated which turns out to be a truncated Gaussian!

\[\begin{align*} &\text{Selection event for Lasso} \\ Ay &\leq b \hspace{1cm} \\ &\text{Truncated Gaussian} \\ F_{\eta^T\mu,\sigma^2 \|\eta\|}^{[V^{-1},V^{+}]}&(\eta^Ty) | \{ A_\lambda \leq b_\lambda \} \sim \text{Unif}(0,1) \\ \forall \eta&\in \mathbb{R}^N \end{align*}\]Where the \(V\) terms are truncated bounds on the Gaussian distribution that are functions of \(\eta,A,b\) and are solvable. Recall that the KKT conditions for the Lasso are of the form: \(X_j^T(y-X\beta\hat) = \text{sign}(\beta_j)\lambda\) if the \(j^{th}\) feature is selected, and the \(A\) matrix and \(b\) vector can be used to reflect this. Because Tibshirani and Friedman have been highly influential in developing the Selective Inference tools, they of course have an R package selectiveInference on CRAN.

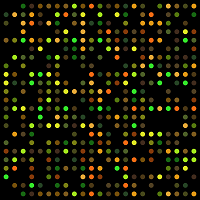

Why is this approach conceivable better than univariate tests? Recall that the potential bias that was seen in equation \eqref{eq:gen3} may be lessened if variables are simultaneously conditioned on. Let’s compare the true discovery rate from a univariate test where \(p=50\), \(m=10\), \(N=50\), and where the non-causal variables are correlated to the causal elements (i.e. \(\gamma_{kj}\neq 0\)).

N <- 50

p <- 50

m <- 10

mu <- rep(0,p)

Sigma <- matrix(0.25,nrow=p,ncol=p) + diag(rep(0.75,p))

Beta <- c(rep(1,m),rep(0,p-m))

library(MASS)

library(selectiveInference)

nsim <- 250

tdr.mat <- matrix(NA,nrow=nsim,ncol=2)

for (k in 1:nsim) {

set.seed(k)

X <- mvrnorm(N,mu,Sigma)

XScale <- scale(X)

Y <- as.vector(X %*% Beta) + rnorm(N)

pval.uni <- apply(X,2,function(cc) summary(lm(Y ~ cc))$coef[8] )

pval.uni.adjust <- p.adjust(pval.uni,'fdr')

tdr.uni <- sum(pval.uni.adjust[1:m] < 0.05)/sum(pval.uni.adjust < 0.05)

lam.lasso <- N

mdl.lasso <- glmnet(X,Y,'gaussian',lambda = lam.lasso/N,standardize = F,thresh = 1e-20)

bhat.lasso <- coef(mdl.lasso,exact=TRUE)[-1]

supp.lasso <- which(bhat.lasso !=0)

sighat <- summary(lm(Y ~ X[,supp.lasso]))$sigma

mdl.si <- tryCatch(fixedLassoInf(XScale,Y,bhat.lasso,lam.lasso,sigma = sighat),error=function(e) NA)

if (class(mdl.si) == 'fixedLassoInf') {

supp.lasso <- mdl.si$vars

pval.si <- mdl.si$pv

} else {

supp.lasso <- rep(1,p)

pval.si <- rep(1,p)

}

pval.lasso <- rep(1,p)

pval.lasso[supp.lasso] <- pval.si

tdr.lasso <- sum(pval.lasso[1:m] < 0.05)/sum(pval.lasso < 0.05)

tdr.mat[k,] <- c(tdr.uni,tdr.lasso)

}

tdr.sum <- apply(tdr.mat,2,mean,na.rm=T)

print(sprintf('True discovery rates: univariate=%0.2f, Lasso=%0.2f',tdr.sum[1],tdr.sum[2]))## [1] "True discovery rates: univariate=0.22, Lasso=0.85"This results are quite impressive! Out of the statistically significant features, 85% of them are true positives for the Lasso, compared to only 22% for the univariate approach. Keep in mind that the univariate approach is still rejecting the null hypothesis of no effect for the true positives most of the time, but is overwhelmed by the false positives. In the genomic situation it may be the case that the primary concern is power and not false positives, and therefore the univariate approach would be less problematic. However there are no guarantees that this will always be the case because the direction of the omitted variable bias may actually push the univariate coefficients towards zero for the true positives. As the size of datasets in bioinformatics continues to grow, the selective inference technique will become increasingly useful.

References

-

LD just refers to any pair/network of variants that are likely to be inherited together. In other words, if by knowing your genotype at position A, I am also given some information as to your genotype at position B, these two loci are said to be in LD. ↩

-

All this means is that the sequence of base pairs found at a given region of the genome is determined for each individual. ↩

-

Since the human genome is fully sequenced, we can compare how your base pairing looks at say Chromosome 1, position 1,875,476 compared to the reference. If the reference is say {C,C} and you are {C,T} then you’d be encoded as have one allele. Although technically allele is just an alternative form, so it’s more accurate to say the number of alternative alleles relative to the reference. ↩

-

Dominant because having one allele is sufficient to cause a phenotypic effect (rather than recessive which would require two alleles to have an impact) and additive because having two alleles has twice the impact of one. Many other plausible genetic models could be assumed as well. ↩

-

Technically the Lasso does not even need to solve the solution path for all the variables due to some Strong Discarding Rules but these are nevertheless calculated with the response and design matrix. ↩