Computational tools to support enciphered poetry

Please note that Heroku no longer provides free hosting of Dash apps and the links to the application in this post are currently not working. I am looking into alternative free hosting services.

Overview

In cryptography, substitution ciphers are considered a weak form of encryption because the ciphertext shares the same empirical distribution of the plaintext language used to write the message. This allows the cipher to be easily cracked. Despite being a poor form of encryption, substitution ciphers present an interesting opportunity to write constrained poems that can be read in two different ways. For example, with the following cipher key $\frac{\text{i}}{\text{w}}\frac{\text{n}}{\text{o}}\frac{\text{e}}{\text{l}}\frac{\text{r}}{\text{s}}\frac{\text{d}}{\text{t}}$, the expression below can be read interchangeably:

inner world

wools inset

To be able to write poems effectively with a substitution cipher, it is desirable to have a dictionary of actual words in a plaintext/ciphertext combination (hereafter referred to as an “enciphered dictionary”). Here is an app that demonstrates what this looks like.

Figure 1: Heroku/dash app

The number of enciphered dictionaries that exists depends on a combinatorial process. When using all 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, there are almost 8 trillion combinations of letter pairings. In contrast, when using 12 letters there are only 15 thousand combinations.

The goal of this post is three-fold:

- Provide an overview of constrained poetry and enciphered poems

- Develop

pythonclasses to be able to find enciphered dictionaries - Deploy a web-based application that allows a poet to easily navigate the enciphered dictionary.

While the code in this post can be run in a self-contained jupyter notebook, the full code and conda environment for this post can be found here. The rest of this post is outlined as follows.

- Section (1) gives a background of the use of constraints in poetry

- Section (2) provides a background on enciphered poetry

- Section (3) gives the

pythoncode needed to find an enciphered dictionary - Section (4) links to a template that creates an interactive tool hosted on

dashandheroku

After I finished this post I realized that Peterson and Fyshe (2016) had already undertaken a similar exercise. Their work is much more academic and uses a beam search approach to explore the combinatorial space of substitution ciphers in a way that is linked to n-gram word frequencies. This is a clever way to avoid having to do a brute-force search over the space. This post can be thought of as slightly less technical analysis with code that can be run within a single jupyter notebook environment. It also provides a way to create an interactive app. Our two projects are therefore complementary of each other.

(1) The use of constraints in poetry

Constraints in poetry are as old as the artform itself. Rhyme schemes, meter, and poetic forms (e.g. sonnets) all impose constraints on what words can be used in what order. Yet far from limiting the expressive capacity of poetry, constraints often help to bring out what is most beautiful in human language. The constraint most associated with poetry is rhyming. In the late Victorian era poets like Tennyson had perfected this technique:

By the margin, willow-veil’d,

Slide the heavy barges trail’d

By slow horses; an unhail’d

The shallop flitteth silken-sail’d

Skimming down to Camelot

…

Though the mellifluous feel of Victorian-era poetry could sometimes be overwrought, it demonstrates that the rhyming constraint can be a necessary condition to achieving a certain feel in a poem. Modernist poets like TS Eliot and Ezra Pound moved away from what Milton presciently referred to as the “the jingling sound of like endings” to a more fluid and unstructured type of poetry. The poetic world has rarely looked back. Consider the most popular book of poetry (by far) in the 21st century: Rupi Kaur’s milk and honey. The book is full of beautiful and sparse poetry, yet it has very little rigid structure, and instead is shaped (literally) by the emotional cadence of the sexual trauma the book is based on.

Like Newton’s third law, all changes in artistic direction are met with a counter-reaction. The Oulipo movement, which began in the 1960s, attempted to explore the limits of what could be produced under increasingly rigorous restrictions. Made up of mainly French-speaking writers and mathematicians, Oulipo were described as “rats who construct the labyrinth from which they plan to escape.” For example, Perec’s La Disparition was a novel written without the letter e (i.e. a lipogram).

Today, there are a small number of contemporary poets whose artistic oeuvre is centred around constraint-based poetry. This includes Christian Bök, Anthony Etherin, and Luke Bradford. These poets are also interested in science and how computational tools can help explore the edge cases of poetic expression.[1] Below are some poetic examples from each poet using three different constraint-based techniques: tetragrams, univocalics, and anagrams.

Luke Bradford

She’s aged well past what rock lies near that seat;

Like some Myth,

She’s been dead many eons;

She’s seen what amid that long dark lies;

…

Mona Lisa (Tetragrams)

Christian Bök

Enfettered, these sentences repress free speech. The text deletes selected letters. We see the revered exegete reject metred verse: the sestet, the tercet…

…

Euonia (Chapter E)

Anthony Etherin

I wandered lonely as a cloud…

All law worn. I seduced an ode,

a lucid yarn so seed allowed…

…

For Wordsworth (Anagram)

Though the constraint-based poets today know they are a niche group within a niche art form, their artistic stance actually represents an ongoing debate in poetry for the last 200 years between the egotistical sublime and negative capability.[2] The former views the job of the poet as providing a confessional outpouring of feeling; an inner monologue of thoughts and experiences. The latter believes that the poet is merely an instrument which channels other forces which speak through them; treating language as an alien form to engineer for human purposes. Most contemporary poets subscribe to the philosophy of the egotistical sublime.

For poets like Bök, this obsession of internal reflection and expression, while appropriate in some measure, has consumed contemporary poetic culture to an unhealthy degree.

I think the greatest way to impugn poetry is simply to note that even though humans have set foot on the moon, there is no canonical poem about that moment. And you can bet that if the ancient Greeks had ridden a trireme to the moon, there would be a 12-volume epic poem about that grandiose adventure.

To a casual reader of poetry, the first encounter with a constraint-based poem will often produce a satisfying feel generated from the felicitous effect of the structure. Until one has read Bök’s Eunoia, no English speaker can truly appreciate the personality of each vowel. Only by constraining ourselves do we learn that e is regal and languid, i is shrill and staccato, u is guttural and dirty, etc.

One of the most ancient forms of constrained poetry is the lipogram in which certain letter(s) are avoided (which dates to the 6th century BC). Lipograms are a beautiful demonstration of how subtracting elements can actually serve to enhance a poem in the right context. An interesting analogy from music world is the Köln Concert where Keith Jarrett had to play on an old piano where some of the keys were broken. This sounds produced by this “lipogrammatic piano” have a sui generis feel due to its uniquely limited range.

(2) Enciphered poems

Substitution ciphers in cryptography are designed to hide the meaning of a message, with a critical distinction between the plaintext and the ciphertext for this reason. In contrast, an enciphered poem (usually) does not distinguish between what poem is encrypted and what is decrypted.[3] Although, there may be a more obvious choice of which poem is meant to be read first (e.g. a call and response). Here is an example of a (rather abstract) poem I wrote using a total of 12 letters and the following cipher $\frac{\text{e}}{\text{o}}\frac{\text{t}}{\text{c}}\frac{\text{a}}{\text{i}}\frac{\text{s}}{\text{h}}\frac{\text{n}}{\text{d}}\frac{\text{r}}{\text{l}}$.

An ID acts, he roots

Id, an itch so leech

Even though the semantic sense of this poem is limited, there are some elements that make it interesting. “Id”, “itch”, and “leech” suggests something innate and animalistic. “ID”, “acts”, and “roots” hints at a heroic defence. While an element of pareidolia exists when reading these sorts of poems (perceiving patterns in noise), a good constraint-based poem can encourage the imagination by structuring itself in a grammatically correct way. This is why a poem like the Jabberwocky continues to be loved. “An ID acts, he roots” follows the proper structure of a sentence: “article noun verb, pronoun verb” like “A hero acts, he defies”. For this toy poem, there is obvious order of which sentence should be read first.

A substitution cipher closely resembles how DNA works. The foundational structure of all biological organisms is made up of four nucleotides: adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T). Each nucleotide pairs with one other counterpart (A to T and C to G). For example a sequence of the nucleotides A-C-G-T-A-G will be “zipped up” with T-G-C-A-T-C and vice versa. This is why DNA is double-stranded. While natural languages and genetic languages both have “letters”, they are used in slightly different ways. In human language, a certain combination of letters forms a word, and a certain order of words forms a sentence. In DNA, different triplets of nucleotides form a codon and associated amino acid, and a certain order of amino acids forms a protein.[4]

There are a total of 64 codons ($4^3$ combinations of triplets) and 20 amino acids, meaning there is a many-to-one mapping of codons to amino acids. One approach to having an enciphered poem in a biological organism is to have the codons in DNA/mRNA represent a letter and the corresponding amino acid expressed by the organism as another letter. For example, suppose we wanted to have “a” pair with “i” in a substitution cipher. If we assign the triplets TCT/TCC/TCA/TCG to represent “a”, then whenever we see the amino acid serine in a protein we will know it is an “i”.

This approach of a codon/amino acid substitution cipher has actually been carried out in Christian Bök’s Xenotext project. While the project has been successfully implemented using a simple bacteria, the goal is to have the poem embedded in the extremophile organism Deinococcus radiodurans. Affectionately nicknamed Conan the Bacterium, this organism has the most robust genetic repair mechanism found in the biological world. If the bacterium’s DNA was successfully modified to encode a poem, it is likely that it would remain unmodified from mutations for hundreds of millions of years.

Bök’s actual poem, titled Orpheus and Eurydice from the Xenotext is shown below. It is a beautiful poem in the tradition of a pastoral dialogue between two lovers.[5] You may also notice that the poem uses only 20 letters (the pairs b:v, j:x, q:z are never used). This is because there are only 20 amino acids (plus a stop codon to denote a space).

Figure 2: Orpheus and Eurydice

Before writing an enciphered poem one needs to decide the dictionary of eligible words. A dictionary like Webster’s or the OED will have over 470K English words, although many of these will be proper nouns like Athens or archaic words like crumpet. Yet even these expansive dictionaries will lack many technical words used in specific disciplines. An appropriate choice of dictionary is important for writing different styles of poems. After a dictionary has been chosen, it can be further subset by imposing a lipogrammatic constraint as discussed in section (1). Using lipograms reduces the search space of letter pairings and also amplifies the intensity of the constraint.

For a given choice of $k$ even-numbered letters there are a total of $\prod_{i=1}^{k/2} (2i-1)$ possible ciphers. If there were four letters a, b, c, d, then a total of 3 unique enciphers exist: (i) a:b, c:d, (ii) a:c, b:d, (iii) a:d, b:c. Because the cipher is complementary, a:b is the same as b:a (in this sense it is akin to combination rather than a permutation).

Imagine you are going to pick a cipher based on 4 letters. After picking an initial letter, there are three choices you can make. After these first two letters are paired, you pick another letter. There is only one way to pair it. Hence three times one equals three combinations. Why are we counting a choice only after a letter has been picked? The reason is the complementarity of the letter. If you have two letters, it doesn’t matter if you pick the first one and then second one, or vice versa. Hence, the only real “choice” is after a letter has been selected.

In addition to the number of ways $k$ letters can be paired, there are $26 \choose k$ possible sets of letters for a given lipogrammatic cipher. The first code block below will use a simple function to show how many possible encodings can exist for a given number of letters.

# Load modules needed for rest of post

import os

import io

import nltk

import string

import contextlib

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import plotnine as pn

from scipy.special import comb

import spacy

nlp_sm = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

from funs_support import makeifnot

letters = [l for l in string.ascii_lowercase]

def n_encipher(n_letters):

assert n_letters % 2 == 0, 'n_letters is not even'

n1 = int(np.prod(np.arange(1,n_letters,2)))

n2 = int(comb(26, n_letters))

n_tot = n1 * n2

res = pd.DataFrame({'n_letter':n_letters,'n_encipher':n1, 'n_lipogram':n2, 'n_total':n_tot},index=[0])

return res

n_letter_seq = np.arange(2,26+1,2).astype(int)

holder = []

for n_letter in n_letter_seq:

holder.append(n_encipher(n_letter))

df_ncomb = pd.concat(holder).reset_index(drop=True)

df_ncomb.style.format("{:,}")

| n_letter | n_encipher | n_lipogram | n_total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 325 | 325 |

| 4 | 3 | 14,950 | 44,850 |

| 6 | 15 | 230,230 | 3,453,450 |

| 8 | 105 | 1,562,275 | 164,038,875 |

| 10 | 945 | 5,311,735 | 5,019,589,575 |

| 12 | 10,395 | 9,657,700 | 100,391,791,500 |

| 14 | 135,135 | 9,657,700 | 1,305,093,289,500 |

| 16 | 2,027,025 | 5,311,735 | 10,767,019,638,375 |

| 18 | 34,459,425 | 1,562,275 | 53,835,098,191,875 |

| 20 | 654,729,075 | 230,230 | 150,738,274,937,250 |

| 22 | 13,749,310,575 | 14,950 | 205,552,193,096,250 |

| 24 | 316,234,143,225 | 325 | 102,776,096,548,125 |

| 26 | 7,905,853,580,625 | 1 | 7,905,853,580,625 |

Using all 26 letters of the Roman alphabet, Table 1 shows that there are almost 8 trillion possible ways the create complementary pairings for 26 letters (n_encipher). However, there are more than 205 trillion possible lipogrammatic ciphers when using 22 letters of the English alphabet because there are 13 billion possible pairings with a further 15 thousand possible sets of 22 letters. Even using only 6 letters there will be more than 3 million possible lipogrammatic ciphers.

To provide actual examples of enciphered dictionaries I’m going to use a simple English dictionary of around 58K words. This will also be combined with data on the empirical distribution of 1-word n-grams to help weight the quality of different dictionaries.

dir_code = os.getcwd()

dir_data = os.path.join(dir_code, '..', 'data')

makeifnot(dir_data)

dir_output = os.path.join(dir_code, '..', 'output')

makeifnot(dir_output)

path_ngram = os.path.join(dir_data,'words_ngram.txt')

if not os.path.exists(path_ngram):

os.system('wget -q -O %s/words_ngram.txt https://norvig.com/ngrams/count_1w.txt' % path_ngram)

path_words = os.path.join(dir_data,'words_corncob.txt')

if not os.path.exists(path_words):

print('Downloading')

os.system('wget -q -O %s/words_corncob.txt http://www.mieliestronk.com/corncob_lowercase.txt' % path_words)

# (1) Load the Ngrams

df_ngram = pd.read_csv(path_ngram,sep='\t',header=None).rename(columns={0:'word',1:'n'})

df_ngram = df_ngram[~df_ngram['word'].isnull()].reset_index(drop=True)

# (2) Load the short word set

df_words = pd.read_csv(path_words,sep='\n',header=None).rename(columns={0:'word'})

df_words = df_words[~df_words['word'].isnull()].reset_index(drop=True)

# Overlap?

n_overlap = df_words.word.isin(df_ngram['word']).sum()

print('A total of %i short words overlap (out of %i)' % (n_overlap, df_words.shape[0]))

# Merge datasets in the intersection

df_merge = df_ngram.merge(df_words,'inner','word')

df_merge = df_merge.assign(n_sqrt=lambda x: np.sqrt(x['n']), n_log=lambda x: np.log(x['n']))

A total of 51886 short words overlap (out of 58109)

We can see that there is an 89% overlap between the words in the dictionary and the word usage data that was downloaded. Next, we can add on the different parts of the speech such as nouns, adverbs, etc.

# Capture print outupt

def capture(fun,arg):

f = io.StringIO()

with contextlib.redirect_stdout(f):

fun(arg)

output = f.getvalue()

return output

# Add on the parts of speech

pos_lst = [z[1] for z in nltk.pos_tag(df_merge['word'].to_list())]

df_merge.insert(1,'pos',pos_lst)

# Get PoS defintions

pos_def = pd.Series([capture(nltk.help.upenn_tagset,p) for p in df_merge['pos'].unique()])

pos_def = pos_def.str.split('\\:\\s|\\n',expand=True,n=3).iloc[:,:2]

pos_def.rename(columns={0:'pos',1:'def'},inplace=True)

df_merge = df_merge.merge(pos_def, 'left', 'pos')

We can see what the most and least common words are according to the n-gram frequency.

print('The ten most and least common words in the dictionary')

pd.concat([df_merge.head(10)[['word','n']].reset_index(None,True),

df_merge.tail(10)[['word','n']].reset_index(None,True)],1)

The ten most and least common words in the dictionary

Unsurprisingly the articles “the”, “of”, “and” dominate word usage, whilst Scrabble words like “expurgated” or “sibilance” are used only a handful of times (relatively speaking).

| word | n | word | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| the | 23135851162 | offcuts | 12748 |

| of | 13151942776 | hinderer | 12737 |

| and | 12997637966 | eminences | 12734 |

| to | 12136980858 | vaporisation | 12732 |

| in | 8469404971 | expurgated | 12732 |

| for | 5933321709 | concussed | 12732 |

| is | 4705743816 | griever | 12729 |

| on | 3750423199 | sibilance | 12720 |

| that | 3400031103 | synchronises | 12719 |

| by | 3350048871 | insatiably | 12717 |

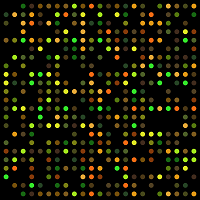

Figure 3 below shows the empirical distribution of word usage over all 52K words. Notice that the distribution is heavily skewed to the right. Even the log-transformation of word usage is polynomial suggesting a doubly-exponential distribution.

Word usage frequencies help to weight the final quality of the enciphered dictionary. For example, one dictionary might have 50 words that are frequently used in English, whilst another might have 100 that are rarely used. By weighting the total number of words, we might come to a different conclusion about which is the “preferred” dictionary in terms of the quality of word choices to build poems from. If the weights are based on the log-transformed count of frequencies this will be more favourable to dictionaries with more words, while using the untransformed frequencies will favour any dictionary that has one or more top words.

# Examine the score frequency by percentiles

p_seq = np.arange(0.01,1,0.01)

dat_n_q = df_merge.melt('word',['n','n_sqrt','n_log'],'tt')

dat_n_q = dat_n_q.groupby('tt').value.quantile(p_seq).reset_index()

dat_n_q.rename(columns={'level_1':'qq'}, inplace=True)

dat_n_q.tt = pd.Categorical(dat_n_q.tt,['n','n_sqrt','n_log'])

di_tt = {'n':'count', 'sqrt(count)':'sqrt','n_log':'log(count)'}

(pn.ggplot(dat_n_q, pn.aes(x='qq',y='value')) + pn.geom_path() +

pn.theme_bw() + pn.facet_wrap('~tt',scales='free_y') +

pn.labs(y='Weight', x='Quantile') +

pn.theme(subplots_adjust={'wspace': 0.25}))

Figure 3: Distribution of score weightings

For a lipogrammatic cipher, we may want to focus on letters that show up most commonly in the English language. According to our dictionary the top-12 letters are: e, t, o, a, i, s, n, r, l, c, h, d.

letter_freq = df_merge[['word','n']].apply(lambda x: list(x.word),1).reset_index().explode(0)

letter_freq.rename(columns={0:'letter','index':'idx'}, inplace=True)

letter_freq_n = letter_freq.merge(df_merge.rename_axis('idx').n.reset_index()).groupby('letter').n.sum().reset_index()

letter_freq_n = letter_freq_n.sort_values('n',ascending=False).reset_index(None,True)

print(letter_freq_n.head(12))

letter n

1 e 312191856406

2 t 225437874527

3 o 201398083835

4 a 198476530159

5 i 192368122407

6 s 181243649705

7 n 179959338059

8 r 176716148797

9 l 109383119821

10 c 96701494588

11 h 95559527823

12 d 93460670221

(3) Computational tools to support enciphered poems

After the order of the lipogrammatic constraint is determined ($k$), there are two combinations on interest:

- The $26 \choose k$ possible ways to select $k$ even-numbered letters

- The $\prod_{i=1}^{k/2} (2i-1)=1\cdot 3 \cdot \dots \cdot (k-1)$ possible ways to make an encipherment through the complementary letter pairing

There are three practical computational questions that need to be answered. First, after choosing the number of letters ($k$), how do we iterate through all possible combinations in a deterministic way? Second, for a given set of actual letters (e.g. etoaisnrlchd), how to do we iterate through all possible pairings in a deterministic way? Lastly, after the alphabet and pairing has been decided (e.g. a:s, h:o), how can we determine which words are valid for encipherment? The encipherer class below provides convenient wrappers for each of these three questions.

A few notes about the methods of the class to better understand what it is doing. The class needs to be initialized with a DataFrame df_english and an index of which column has the words cn_word. Next, the choice of letters needs to be set with set_letters. This can either be manually specified (letters='abcd...'), or decided by the deterministic procedure (idx_letters=5468). After the letters have been established (i.e. the lipogram), then set_encipher will determine the letter pairing by either manual specification (letters='a:b,c:d,...') or deterministically with an index (idx_pairing=4681). To actually determine the valid word overlap, the method get_corpus() can be run. To do a brute-force search over the best idx_pairing, the method score_ciphers can be called with a corresponding weight column (cn_weight) that was found in the original df_english DataFrame. Note that when setting idx_letters or idx_pairing, it is worthwhile to consult the idx_max attribute, as this shows the maximum value the index can range up to.

"""

df_english: A DataFrame with a column of words (and other annotations)

cn_word: Column name in df_english with the English words

letters: A string of letters (e.g. "abqz")

n_letters: If letters is None, how many letters to pick from

idx_letters: If letters is None, which combination index to pick from

"""

class encipherer():

def __init__(self, df_english, cn_word):

assert isinstance(df_english, pd.DataFrame), 'df_english needs to be a DataFrame'

self.df_english = df_english.rename(columns={cn_word:'word'}).drop_duplicates()

assert not self.df_english['word'].duplicated().any(), 'Duplicate words found'

self.df_english['word'] = self.df_english['word'].str.lower()

self.latin = string.ascii_lowercase

self.n = len(self.latin)

"""

After class has been initialized, letters must be chosen. This can be done by either manually specifying the letters, or picking from (26 n_letters)

letters: String (e.g. 'aBcd')

n_letters: Number of letters to use (must be ≤ 26)

idx_letters: When letters is not specified, which of the combination indices to use from (n C k) choices

"""

def set_letters(self, letters=None, n_letters=None, idx_letters=None):

if letters is not None:

assert isinstance(letters, str), 'Letters needs to be a string'

self.letters = pd.Series([letter.lower() for letter in letters])

self.letters = self.letters.drop_duplicates()

self.letters = self.letters.sort_values().reset_index(drop=True)

self.n_letters = self.letters.shape[0]

self.idx_max = {k:v[0] for k,v, in self.n_encipher(self.n_letters).to_dict().items()}

else:

has_n = n_letters is not None

has_idx = idx_letters is not None

assert has_n and has_idx, 'If letters is None, n_letters and idx_letters must be provided'

self.idx_max = {k:v[0] for k,v, in self.n_encipher(n_letters).to_dict().items()}

assert idx_letters <= self.idx_max['n_lipogram'], 'idx_letters must be ≤ %i' % self.idx_max['n_lipogram']

assert idx_letters > 0, 'idx_letters must be > 0'

self.n_letters = n_letters

tmp_idx = self.get_comb_idx(idx_letters, self.n, self.n_letters)

self.letters = pd.Series([self.latin[idx-1] for idx in tmp_idx])

self.letters = self.letters.sort_values().reset_index(drop=True)

assert self.n_letters % 2 == 0, 'n_letters must be an even number'

assert self.n_letters <= self.n, 'n_letters must be ≤ %i' % self.n

self.k = int(self.n_letters/2)

"""

After letters have been set, either specify mapping or pick from an index

pairing: String specifying pairing order (e.g. 'a:e, i:o')

idx_pairing: If the pairing is not provided, pick one of the 1 to n_encipher possible permutations

"""

def set_encipher(self, pairing=None, idx_pairing=None):

if pairing is not None:

assert isinstance(pairing, str), 'pairing needs to be a string'

lst_pairing = pairing.replace(' ','').split(',')

self.mat_pairing = np.array([pair.split(':') for pair in lst_pairing])

assert self.k == self.mat_pairing.shape[0], 'number of rows does not equal k: %i' % self.k

assert self.mat_pairing.shape[1] == 2, 'mat_pairing does not have 2 columns'

tmp_letters = self.mat_pairing.flatten()

n_tmp = len(tmp_letters)

assert n_tmp == self.n_letters, 'The pairing list does not match number of letters: %i to %i' % (n_tmp, self.n_letters)

lst_miss = np.setdiff1d(self.letters, tmp_letters)

assert len(lst_miss) == 0, 'pairing does not have these letters: %s' % lst_miss

else:

assert idx_pairing > 0, 'idx_pairing must be > 0'

assert idx_pairing <= self.idx_max['n_encipher'], 'idx_pairing must be ≤ %i' % self.idx_max['n_encipher']

# Apply determinstic formula

self.mat_pairing = self.get_encipher_idx(idx_pairing)

# Pre-calculated values for alpha_trans() method

s1 = ''.join(self.mat_pairing[:,0])

s2 = ''.join(self.mat_pairing[:,1])

self.trans = str.maketrans(s1+s2, s2+s1)

self.str_pairing = pd.DataFrame(self.mat_pairing)

self.str_pairing = ','.join(self.str_pairing.apply(lambda x: x[0]+':'+x[1],1))

"""

Find enciphered corpus

"""

def get_corpus(self):

words = self.df_english['word']

# Remove words that have a letter outside of the lipogram

regex_lipo = '[^%s]' % ''.join(self.letters)

words = words[~words.str.contains(regex_lipo)].reset_index(drop=True)

words_trans = self.alpha_trans(words)

idx_match = words.isin(words_trans)

tmp1 = words[idx_match]

tmp2 = words_trans[idx_match]

self.df_encipher = pd.DataFrame({'word':tmp1,'mirror':tmp2})

self.df_encipher.reset_index(drop=True,inplace=True)

# Add on any other columns from the original dataframe

self.df_encipher = self.df_encipher.merge(self.df_english)

"""

Iterate through all possible cipher combinations

cn_weight: A column from df_english that has a numerical score

set_best: Should the highest scoring index be set for idx_pairing?

"""

def score_ciphers(self, cn_weight, set_best=True):

cn_dtype = self.df_english.dtypes[cn_weight]

assert (cn_dtype == float) | (cn_dtype == int), 'cn_weight needs to be a float/int not %s' % cn_dtype

n_encipher = self.idx_max['n_encipher']

holder = np.zeros([n_encipher,2])

for i in range(1, n_encipher+1):

self.set_encipher(idx_pairing=i)

self.get_corpus()

n_i = self.df_encipher.shape[0]

w_i = self.df_encipher[cn_weight].sum()

holder[i-1] = [n_i, w_i]

# Get the rank

self.df_score = pd.DataFrame(holder,columns=['n_word','weight'])

self.df_score['n_word'] = self.df_score['n_word'].astype(int)

self.df_score = self.df_score.rename_axis('idx').reset_index()

self.df_score['idx'] += 1

self.df_score = self.df_score.sort_values('weight',ascending=False).reset_index(drop=True)

if set_best:

self.set_encipher(idx_pairing=self.df_score['idx'][0])

self.get_corpus()

"""

Deterministically returns encipher

"""

def get_encipher_idx(self, idx):

j = 0

lst = self.letters.to_list()

holder = np.repeat('1',self.n_letters).reshape([self.k, 2])

for i in list(range(self.n_letters-1,0,-2)):

l1 = lst[0]

q, r = divmod(idx, i)

r += 1

l2 = lst[r]

lst.remove(l1)

lst.remove(l2)

holder[j] = [l1, l2]

j += 1

idx = q

return holder

"""

Deterministically return (n C k) indices

"""

@staticmethod

def get_comb_idx(idx, n, k):

c, r, j = [], idx, 0

for s in range(1,k+1):

cs = j+1

while r-comb(n-cs,k-s)>0:

r -= comb(n-cs,k-s)

cs += 1

c.append(cs)

j = cs

return c

"""

Uses mat_pairing to translate the strings

txt: Any string or Series

"""

def alpha_trans(self, txt):

if not isinstance(txt, pd.Series):

txt = pd.Series(txt)

z = txt.str.translate(self.trans)

return z

"""

Function to calculate total number lipogrammatic and enciphering combinations

"""

@staticmethod

def n_encipher(n_letters):

assert n_letters % 2 == 0, 'n_letters is not even'

n1 = int(np.prod(np.arange(1,n_letters,2)))

n2 = int(comb(26, n_letters))

n_tot = n1 * n2

res = pd.DataFrame({'n_letter':n_letters,'n_encipher':n1, 'n_lipogram':n2, 'n_total':n_tot},index=[0])

return res

As a quick sanity check, let’s make sure that set_letters actually gets all the $n \choose 4$=14950 combinations we’d expect from using a subset of 4 letters.

enc = encipherer(df_merge, 'word')

n_lipogram = enc.idx_max['n_lipogram']

# (i) Enumerate through all possible letter pairings

holder = []

for i in range(1, n_lipogram+1):

enc.set_letters(n_letters=4, idx_letters=i)

holder.append(enc.letters)

df_letters = pd.DataFrame(holder)

df_letters.columns = ['l'+str(i+1) for i in range(4)]

assert not df_letters.duplicated().any() # Check that no duplicate values

df_letters

| l1 | l2 | l3 | l4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | a | b | c | d |

| 1 | a | b | c | e |

| 2 | a | b | c | f |

| 3 | a | b | c | g |

| 4 | a | b | c | h |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 14945 | v | w | x | y |

| 14946 | v | w | x | z |

| 14947 | v | w | y | z |

| 14948 | v | x | y | z |

| 14949 | w | x | y | z |

That looks right! Let’s repeat this exercise for 12 letters (a to l) and make sure we can iterate through all $\prod_{i=1}^{6} (2i-1)=10395$ unique ciphers.

enc = encipherer(df_merge, 'word')

enc.set_letters(n_letters=12, idx_letters=1)

n_encipher = enc.idx_max['n_encipher']

holder = []

for i in range(1, n_encipher+1):

enc.set_encipher(idx_pairing=i)

holder.append(enc.mat_pairing.flatten())

df_encipher = pd.DataFrame(holder)

idx_even = df_encipher.columns % 2 == 0

tmp1 = df_encipher.loc[:,idx_even]

tmp2 = df_encipher.loc[:,~idx_even]

tmp2.columns = tmp1.columns

df_encipher = tmp1 + ':' + tmp2

df_encipher.columns = ['sub'+str(i+1) for i in range(6)]

assert not df_encipher.duplicated().any() # Check that no duplicate values

df_encipher

| sub1 | sub2 | sub3 | sub4 | sub5 | sub6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | a:c | b:d | e:f | g:h | i:j | k:l |

| 1 | a:d | b:c | e:f | g:h | i:j | k:l |

| 2 | a:e | b:c | d:f | g:h | i:j | k:l |

| 3 | a:f | b:c | d:e | g:h | i:j | k:l |

| 4 | a:g | b:c | d:e | f:h | i:j | k:l |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 10390 | a:i | b:l | c:k | d:j | e:h | f:g |

| 10391 | a:j | b:l | c:k | d:i | e:h | f:g |

| 10392 | a:k | b:l | c:j | d:i | e:h | f:g |

| 10393 | a:l | b:k | c:j | d:i | e:h | f:g |

| 10394 | a:b | c:d | e:f | g:h | i:j | k:l |

That also looks good. Now combine set_letters, set_encipher, and then get_corpus to actually see the final enciphered dictionary which is stored as the df_encipher attribute.

pd.set_option('display.max_rows', 10)

enc = encipherer(df_merge, 'word')

enc.set_letters(letters='etoaisnrlchd')

enc.set_encipher(idx_pairing=1)

enc.get_corpus()

print(enc.df_encipher[['word','mirror','pos','def']])

print('Character mapping: %s' % enc.str_pairing)

word mirror pos def

0 the sic DT determiner

1 are doc VBP verb, present tense, not 3rd person singular

2 she tic PRP pronoun, personal

3 did aha VBD verb, past tense

4 id ha NN noun, common, singular or mass

.. ... ... ... ...

21 coo err JJ adjective or numeral, ordinal

22 trad soda NN noun, common, singular or mass

23 cots erst NNS noun, common, plural

24 erst cots JJ adjective or numeral, ordinal

25 teds scat NNS noun, common, plural

Character mapping: a:d,c:e,h:i,l:n,o:r,s:t

The quality of different ciphers can be determined by weighting the total number of words by the measure of word frequency. Calling score_ciphers will run deterministically and with a brute-force approach for finding the “best” letter pairing. Note that the code block below will likely take 5-10 minutes to run depending on the computer you are using.

enc = encipherer(df_merge, 'word')

enc.set_letters(letters='etoaisnrlchd')

enc.score_ciphers(cn_weight='n_log',set_best=True)

enc.df_score

| idx | n_word | weight | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 917 | 132 | 2092.352597 | |

| 8936 | 110 | 1797.185035 | |

| 8705 | 108 | 1728.976614 | |

| 818 | 108 | 1709.790184 | |

| 8958 | 104 | 1678.618592 | |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 7302 | 6 | 99.883288 | |

| 7401 | 6 | 99.883288 | |

| 3710 | 6 | 98.803354 | |

| 5263 | 6 | 97.714499 | |

| 5109 | 6 | 97.325101 |

Figure 4: Relationship between log(n-gram) and word count

The figure above shows that using the log of the word frequency leads to a very tight correlation between the number of words and the weighted value of the dictionary (as is expected).

Figure 5: Distribution of word counts and scores

The number of words which ranges from 6 to 132 as can be seen in the figure above. As a reminder, this is only for the ciphers satisfying the 12-letter lipogrammatic constraint of etoaisnrlchd. Lastly, Figure 6 below shows the estimated intercept for the different letter pairings. Most letter pairs are improvements over the default a:c mapping, with s:t being the most effective (on average) whilst i:t is quite poor. The actual distribution of word frequencies is fairly close to the intercept estimate (see this figure).

Figure 6: Intercept for letter pair dummies

(4) Interactive app

To be able write enciphered poems effectively, it is helpful to be able to display the enciphered dictionary in a readable and interactive way. The easiest to do this in python is to build a Dash app, and then deploy it on the web using Heroku. The official documentation from both sources provides a useful backgrouner on this (see here and here). Assuming you have configured git and heroku for the command line, I have written a helpful script to allow you to host your own app:

git clone https://github.com/ErikinBC/bok12_heroku.git

bash gen_dash.sh -l [letters] -n [your-apps-name]

The gen_dash bash file will build the necessary conda environment, create the encipherer class, score all the ciphers, and then push the needed code to Heroku to be compiled. I recommend first trying to build a very simple app that will take about a minute to build by running bash gen_dash.sh -l abcd -n test-app. You can always host the Dash app locally by running python app.py before hosting on Heroku too.

On my laptop it takes several hours to generate the encipherer class with 14 letters and host cipher-poem.herokuapp.com with the command bash gen_dash.sh -l etoaisnrlchdum -n cipher-poem.

The interactive table has seven columns. The first, num, shows the rank-order of the different words by their weighted 1-gram frequency. Notice that I used the minimum weight of the two words. This ensures that if a very common word like “the” gets matched with the acronym “RDA” it won’t receive a high score. The columns word_{xy} show the plaintext and ciphertext with the substitution cipher. The parts-of-speech columns (pos_{xy}) are useful for sorting when trying to find verbs, adjectives, nouns, etc. The definition column def_x also contains the parts of speech, and since these were generated from a different source, it may not always line up with the other columns.

For the app I hosted, there are 135135 different combinations of the substitution cipher possible with 14 letters. Users can change the index by typing the number they want or by using the increment button. The indices are ranked so that 1 has the height sum of weights, and 135135 has the lowest. While the sum of weights is correlated with the number of words, one index may have a higher score with fewer words if those words have more empirical usage from the 1-gram data. Users are encouraged to modify the gen_data.py script if they would like to use a different dictionary or word-frequency usage than the ones I chose.

References

-

All of these poets are published by Penteract Press. ↩

-

For a fuller discussion on this, see a conversation between Christian Bök and Anthony Etherin on the subject. ↩

-

Although this is by no means always true, see Etherin’s Enigma (for Alan M Turing) for an example. ↩

-

This is of course a simplification of both natural language and genetics, but I am trying to make the two systems as simple as possible. ↩

-

See for example The Passionate Shepherd to His Love by Marlowe and Raleigh’s response in The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd. ↩